Deafblindness is often underestimated and misunderstood, and this contributes significantly to the many barriers faced by persons with deafblindness. Some persons with deafblindness are completely deaf and blind, but many have a little sight and/or hearing they can use.

Based on the Nordic definition [3], the WFDB defines deafblindness as a distinct disability arising from a dual sensory impairment of a severity that makes it hard for the impaired senses to compensate for each other. In interaction with barriers in the environment, it affects social life, communication, access to information, orientation and mobility. Enabling inclusion and participation requires accessibility measures and access to specific support services, such as interpreter-guides, among others.

The age of onset of a person’s vision and hearing impairment has a profound impact on the consequences of deafblindness, particularly in relation to communicative development and language acquisition. It is therefore important to differentiate.

- Pre-lingual deafblindness, which describes a vision and hearing impairment acquired at birth or at an early stage in life before the development of language. This may be due to infections during pregnancy, premature birth, birth trauma or genetic conditions (e.g. Down’s syndrome, Usher syndrome, and CHARGE).

- Post-lingual deafblindness, which describes vision and hearing loss acquired following the development of language (spoken or sign language). Deafblindness can be caused by illness, accident or as a result of age-related conditions associated with the loss of vision and hearing (e.g. cataracts, glaucoma and macular degeneration for vision loss, and presbycusis for hearing loss) [4, 5]. While Usher syndrome is an inherited genetic condition, it typically manifests itself (visual and/or hearing loss ) in later childhood or adolescence, following the development of language [6].

Deafblindness is more prevalent among older age groups. However, among children and young adults, deafblindness presents additional implications, impacting on learning and gaining employment.

A DIVERSITY OF BARRIERS AND A DIVERSITY OF SUPPORT REQUIREMENTS

Each person with deafblindness connects, communicates and experiences the world differently. Each individual may face restrictions of participation that are affected by the level of support and barriers in their environment, the severity of the vision and hearing impairment and the age of onset, among other elements. Persons with deafblindness constitute a diversified group with a broad experience of disability and may have different support and inclusion requirements.

It is vital, therefore, that persons with deafblindness access services that meet each individual’s needs and not a combination of services designed for blind or deaf people.

Some persons with deafblindness may experience other functional difficulties and therefore may have additional support needs.

PERSONS WITH DEAFBLINDNESS FREQUENTLY REQUIRE SUPPORT FOR:

COMMUNICATION

There is a variety of techniques and methods of communication support, and there is no standard way of communicating. Communication approaches are likely to vary based on whether a person has pre-lingual or post-lingual deafblindness, which impairment developed first, and the level of residual hearing or sight [7]. For example, people with profound hearing impairments who later develop a visual impairment may still be able to communicate with sign language, with some adaptations. Similarly, people with profound vision impairments who develop hearing impairments may have benefited from braille instruction, but may now require clear speech interpreting. People with pre-lingual deafblindness will use different approaches to acquire language.

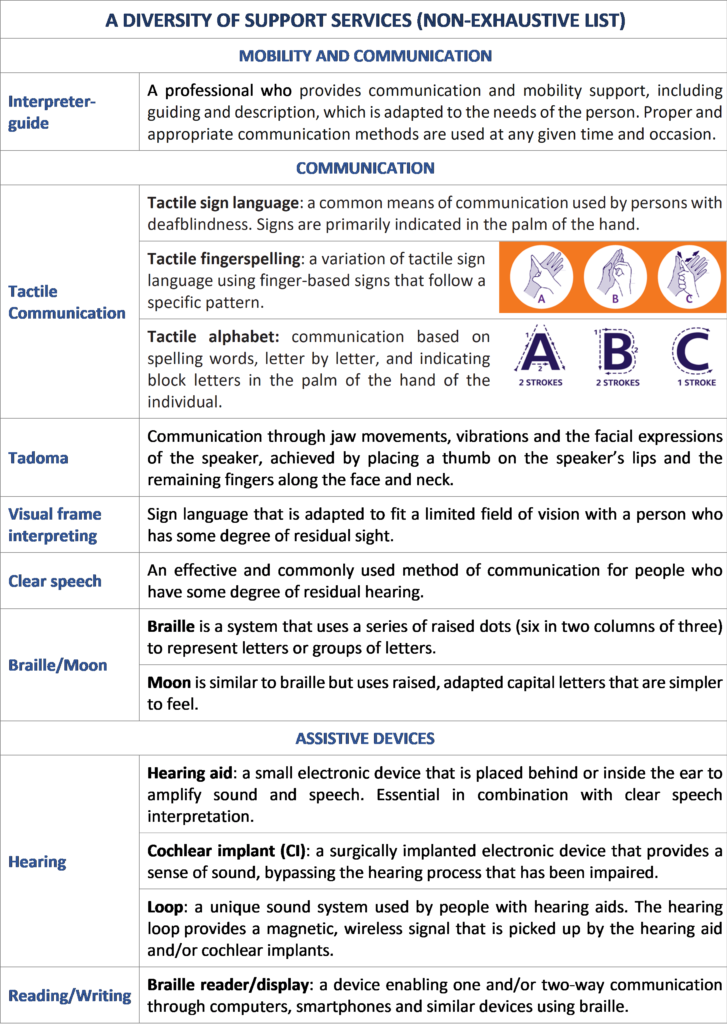

A wide range of communication methods [8] exist, including:

- Tactile interpreting (i.e. tactile sign language to one person with deafblindness) or finger spelling of the manual alphabet.

- Close vision interpreting (i.e. visual sign language within close proximity to a person with deafblindness) or visual frame interpreting (i.e. visual sign language to more than one person with deafblindness).

- Clear speech interpreting (with or without hearing aids) or speech-to-text interpreting (with certain adaptions and with or without technical equipment, such as a computers, large screens and braille displays).

Depending on the person and the situation, any one and/or combination of methods may be required. Furthermore, communication strategies may change over time, particularly if the individual experiences changes in the severity of their hearing and/or visual impairments [9].

Persons with deafblindness may also use assistive technology to support communication. Examples of assistive products include braille displays and writers, hearing aids and loops, and glasses and/or magnifiers. However, it is important to remember that such assistive products will not meet every individual’s needs in all circumstances, and that support may be required in other areas, such as that provided by an interpreter-guide.

MOBILITY

The ability to get around fully and freely is essential to full and effective inclusion and equal participation. For some persons with deafblindness, qualified guiding to support mobility and orientation may be necessary. Guiding is also considered an integral part of interpreter-guide services, as it is not possible to guide and describe for a person with deafblindness without being able to communicate.

DESCRIPTION

In order to fully understand and connect with the environment, some persons with deafblindness choose to use description. This not only encompasses physical surroundings, such as walls and windows, but also occurrences, people and physical objects, including books, posters, and both digital and printed brochures. The WFDB considers description an integral part of any interpreter-guide service. It should be offered at the same time as guiding and interpreting of speech, according to the situation [8].

THE CRITICAL IMPORTANCE OF AN INTERPRETER-GUIDE

While some persons with deafblindness may use communication or basic mobility support in a familiar environment, most will require support from an interpreter-guide in other situations, depending on the circumstances. Interpreter-guide services are truly responsive to the compounded support requirements of persons with deafblindness, both in terms of communication and mobility. The service offers support in line with article 19 of the CRPD, allowing persons with deafblindness to live autonomously and be included in the community. A professional interpreter-guide service can be the key to accessing other services and fundamental rights, such as education, employment, healthcare, culture and recreation.