KEY PRECONDITIONS FOR INCLUSION

RECOGNITION OF DEAFBLINDNESS & THE PROVISION OF SPECIFIC SUPPORT SERVICES

To participate and be included in community, work, education or political life, persons with deafblindness require both the removal of environmental barriers as well as those that prevent access to quality support services. Accessibility features for persons with deafblindness include a wide range of passive accessibility elements related to the built, informational and communicational environment. These features are also common to other persons with disabilities, such as documents being accessible in braille, captioning, tactile patterns on floors, contrasted colours in facilities, loop systems and accessible websites.

However, due to the specific functional restrictions caused by deafblindness, such accessibility features are often insufficient and individual support is required. Through the survey and exchanges at the 2018 Helen Keller World Conference, WFDB members highlighted the lack of awareness and recognition of deafblindness. Indeed, many governments mistakenly assume that services for deaf or blind people are sufficient for persons with deafblindness. Due to the fact that accessibility issues are widely known, this report focuses on two key asks from WFDB members: official recognition of deafblindness and the provision of specific support services.

OFFICIAL RECOGNITION OF PERSONS WITH DEAFBLINDNESS

One of the fundamental asks of WFDB and its members is the recognition of deafblindness by states as well as other international, national and sub-national actors as a distinct disability. In many countries, the absence of such recognition leads to invisibility in statistics, policies, programmes and services, both for the general population and for persons with disabilities. In addition, it contributes to the lack of attention paid to the specific support required by persons with deafblindness across all sectors, perpetuating their exclusion.

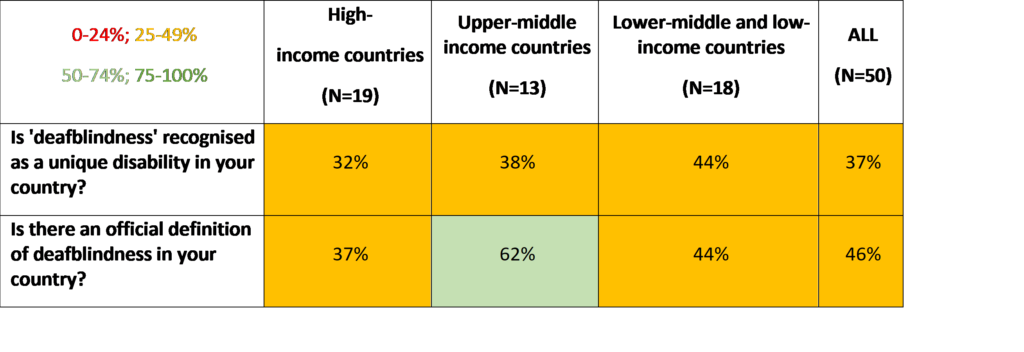

In 2017, WFDB and SI surveyed their members about the official recognition of deafblindness and available support in their country. From the 50 countries for which data was available, 19 (37%) officially recognise deafblindness as a distinct disability. The survey also indicated that countries that do officially recognise deafblindness as a distinct disability and/or have a definition of deafblindness are more likely to provide specific support services. This is particularly the case in low and middle-income countries.

THE VICIOUS CIRCLE: A LACK OF AWARENESS AND A LACK OF RECOGNITION

The majority of WFDB members consulted highlighted the need for greater visibility of deafblindness. Members also suggested the need to raise societal awareness of persons with deafblindness and their communication requirements so that steps can be taken to make society more inclusive.

A vicious circle was identified in relation to the non-recognition of deafblindness whereby a lack of understanding about the diversity and issues faced by persons with deafblindness contributes to a lack of recognition of deafblindness as a unique disability. This, in turn, reinforces their invisibility, lack of awareness and access to support.

“People always think that persons with deafblindness are ‘totally deaf and totally blind’ and we always have to explain! People don’t accept that a person cannot have ‘only’ a combination of both hearing and vision impairment, which creates a unique situation.” (participant at 2018 HKWC consultation)

It was also reported that health and rehabilitation professionals lack an understanding of the situation of persons with deafblindness. For example, professionals often consider people that are not fully deaf and blind as either a deaf person with a visual impairment or a blind person with a hearing impairment. This leads to persons with deafblindness being underestimated and limits the development of adequate support services that are truly responsive to each individual’s specific needs.

In many countries, deafblindness is not considered a standalone disability, and as a result persons with deafblindness are qualified as having multiple disabilities. Some countries, including India through its recent disability rights legislation, acknowledge deafblindness but include it within a multiple disabilities category, thus potentially limiting the positive effect of legal recognition on the development of support services and resource allocation.

Several WFDB members mentioned that, because deafblindness is not recognised in their country, individuals have to select either deaf or blind on official forms and documents, which leads to invisibility in statistical or administrative data. In the EU, as of 2014, only three of the 27 states were collecting official census data regarding the number of persons with deafblindness .

In disability and eligibility determination, a lack of recognition leads to people receiving two separate disability and/or medical certificates. This creates an additional administrative burden and cost for persons with deafblindness and their families.

Where data is available, governments consider persons with deafblindness as a small group that require only the minimum allocation of resources. Again, a lack of understanding about the diversity and extent of communication and support required leads to a significant underestimation of the resources needed to provide appropriate levels of support.

“The government does not support activities or projects for persons with deafblindness because, as it is a small number of people, it cannot show a huge social impact and achieve a significant political return.” (participant at 2018 HKWC consultation)

One recurrent issue is the non-recognition of persons with deafblindness within the disability movement. Whilst there has been progress in recent years, it is still a challenge for organisations of persons with deafblindness to secure adequate resources in many countries, both rich and poor. Once again, a lack of official recognition deprives organisations of persons with deafblindness the necessary resources to carry out much-needed awareness raising and advocacy work.

RECOMMENDATIONS

For national governments:

- Recognise deafblindness as a unique disability in law and practice.

- Raise awareness about the specific situation and requirements of persons with deafblindness.

- Collect and analyse data about the experiences, barriers and support requirements of persons with deafblindness.

- Recognise the specificity of communication systems used by persons with deafblindness.

- Include deafblindness as a specific disability group and facilitate eligibility determination procedures.

- Support organisations of persons with deafblindness to carry out outreach, awareness raising and advocacy.

For DPOs:

- Recognise and include organisations of persons with deafblindness as distinct and integral members of the disability movement.

- Support the official recognition of deafblindness as a unique disability in law and practice.

- Raise the awareness of member states regarding their obligations towards persons with deafblindness under the CRPD.

For the UN and Development Agencies:

- Universal recognition of deafblindness as a unique and distinct disability, including in international classifications.

- Collect and analyse data about the experiences, barriers and support requirements of persons with deafblindness.

- Raise the awareness of member states regarding their obligations towards persons with deafblindness under the CRPD.

- Support the official recognition by member states of deafblindness as a unique disability in law and practice.

- Support organisations of persons with deafblindness to carry out outreach, awareness raising and advocacy work.

ACCESS TO SPECIFIC SUPPORT SERVICES

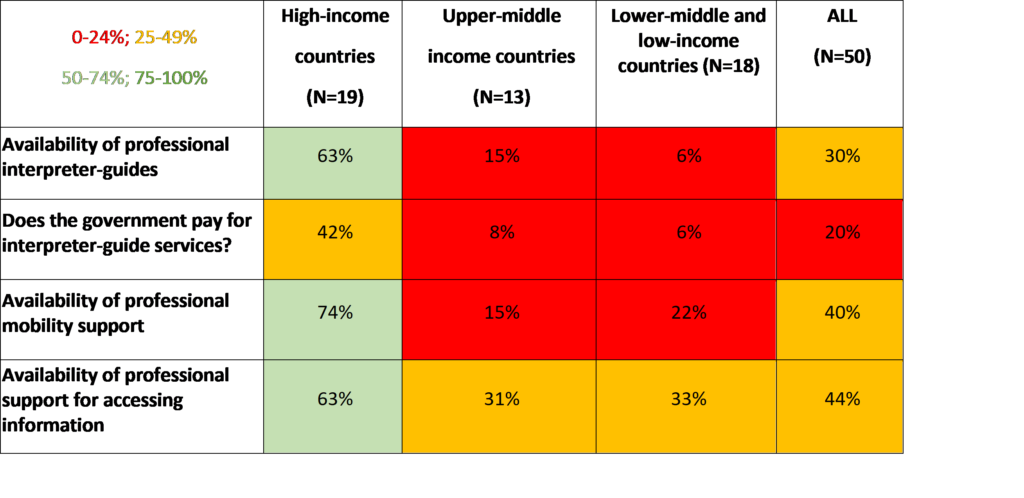

The survey identified a scarcity of services for persons with deafblindness. It is important to note that, even when a service is said to be available, it does not mean that this service is actually available in all areas of the country and in adequate quantity. Services may be provided in some states and/or provinces but not in others, e.g. in urban rather than rural areas.

As expected, support services are far more widely available in high-income countries. However, it is to be noted that interpreter-guides are available in only 58% of high-income countries and 42% provide government-funded interpreter-guide services. The situation is more challenging in low and middle-income countries. Interpreter-guide services are only provided in 10% of countries (N=31; low and upper-middle income countries), with only one country providing government funding. There is, however, higher availability of regular communication and mobility-only services.

An exchange between WFDB members at the 2018 Helen Keller World Conference confirmed the scarcity of interpreter-guide and interpretation services for persons with deafblindness. A lack of awareness and recognition of the specific requirements of persons with deafblindness leads to confusion and an overreliance on specific services for blind and deaf people, which are also limited.

“Sign language is not a communication system, it is a language used by persons that are deaf. For many persons with deafblindness it is part of the communication system that includes other elements, different receptions and emission channels (not only visual but also tactile), creating a system that is tailored to the individual.” (participant at 2018 HKWC consultation)

Good practice does exist, however. In Spain, for instance, Law 27/2007 recognises the specific communication systems used by persons with deafblindness.

In most low and middle-income countries, the few existing services that do exist are concentrated in major cities and there is little to no provision in rural and remote areas. A combined lack of awareness and the relatively small number of persons with deafblindness results in significant underinvestment.

“(…) the government does not realise that some deafblind people need interpreters all day. The government only look at the numbers. They discriminate, and they need to look at us like people and understand our full requirements.” (participant at 2018 HKWC consultation)

The scarcity of resources can lead to competitive behaviour between groups, with service providers for deaf people occasionally monopolising interpretation services to secure funding. In countries such as Croatia, however, effective collaboration takes place between organisations of deaf and deafblind people.

The lack of services severely restricts the social and economic participation of persons with deafblindness, as well as increasing their dependency.

“There are few interpreters and the government does not pay for those services. We have to pay or use family and friends as interpreters. Everyone has to find the guide interpreter to get and keep a job but we have to pay for their services and that takes 50% of a person’s salary.”

Whilst the situation is better in higher-income countries, major issues still exist. Few countries fully recognise and acknowledge the specific requirements of persons with deafblindness, and therefore there remains a lack of adequate services. Where services do exist, the financial support provided by government is often limited and does not adequately cover the work, family and community participation needs of persons with disabilities.

Comments and feedback from WFDB members suggest that the awareness of government decision-makers, proactive DPOs and service providers may be more important than a country’s wealth in terms of the development of appropriate services.

Some countries, including Japan, Australia and a number of Scandinavian nations, have been cited as the most developed in terms of service provision. These countries provide trained interpreter services funded by local, regional and central governments, reflecting the required diversity of services (braille, whisper, sign interpretation and haptic signals, amongst others), as well as offering support in the workplace. However, in many high-income countries, the specificities of deafblindness remain unacknowledged, and as a result support services are either non-existent or insufficient.

Another issue is unequal access to services within countries that have high level of decentralisation, as well as limited access to services. For example, in some areas of certain countries, where the number of hours of interpretation granted to persons with deafblindness have been cut.

Whilst the current situation is unsatisfactory, some progress is being made, and there may be a growing trend towards broader recognition of deafblindness in a number of countries. For example, in situations where national recognition is lacking, some sub-national authorities are taking action. In India, for example, some states have issued certificates specifying deafblindness as a distinct disability, despite the national government categorising the term as a multiple disability.

RECOMMENDATIONS

For countries:

- In line with CRPD, ensure access to support services that facilitate inclusion and independent living, and enable access to information, communication and mobility. This could be achieved by:

- Officially recognising the specificity of accessibility and support service requirements for persons with deafblindness.

- Developing partnerships with DPOs, NGOs and the private sector to ensure the development of support services across sectors.

- Ensuring adequate and sustainable funding for existing and newly created services.

- Ensuring access to affordable and high quality assistive devices.

- Refrain from decreasing the level of support currently provided to persons with deafblindness.

- Increase international cooperation between countries that have developed adequate support systems and those that are willing to engage.

- Include accessibility and non-discrimination requirements in all public procurements, including goods and services, as well as in accreditation and licensing for telecommunication services, amongst others.

For the UN and development agencies:

- Support governments to develop support services, including technical and financial assistance, and facilitate international technological exchange.

- Include accessibility and non-discrimination requirements in public procurement regulations.