WHAT DOES THE DATA SAY?

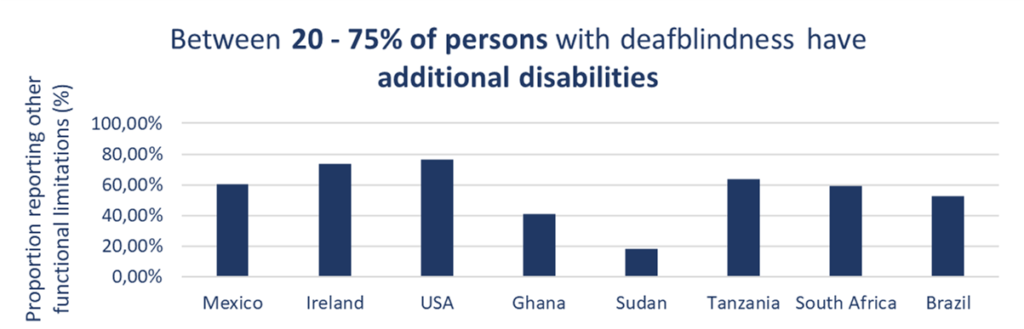

The country analyses provided little data on health status and access to healthcare. The only indicator of health status was the presence of additional disabilities. Figure 9 shows the proportion of persons with deafblindness with other functional difficulties in each dataset. Between 20% and 75% of persons with deafblindness reported functional difficulties, such as mobility and cognition, and the presence of other functional difficulties remained high across all age groups, including children. Multi-morbidity among children and adults with deafblindness was also reflected in the literature review. For example, among children with deafblindness in Montreal, Canada, 86% had additional disabilities [25].

The literature review also found evidence that persons with deafblindness may experience poorer levels of health and barriers to accessing health services. These studies are, however, mostly restricted to high-income settings. For example, persons with deafblindness reported poorer self-rated health in the United States and Japan [14, 27, 28], as well as increased mortality rates [29-31]. Common challenges to accessing both general health and rehabilitation services included: a lack of accommodations in health facilities, particularly in terms of accessible information and alternative forms of communication; costs of accessing care, as insurance often does not always cover all expenses; concentration of services in cities, with little available in rural areas; and a lack of knowledge of and training on deafblindness among health professionals [12, 32].

There is also a growing body of research demonstrating that persons with deafblindness are more likely to experience depression and other mental health conditions compared to both people without sensory impairments or with visual or hearing impairment alone [13, 33-39]. Persons with deafblindness often experience barriers to accessing mental health services. For example, in the UK, 60% of persons with deafblindness surveyed reported experiencing psychological distress, while only 5% said that they had access to mental health services [33]. Similarly, in the United States, only 16% of mental health service providers had procedures in place to accommodate persons with deafblindness [40].

OUR VOICE

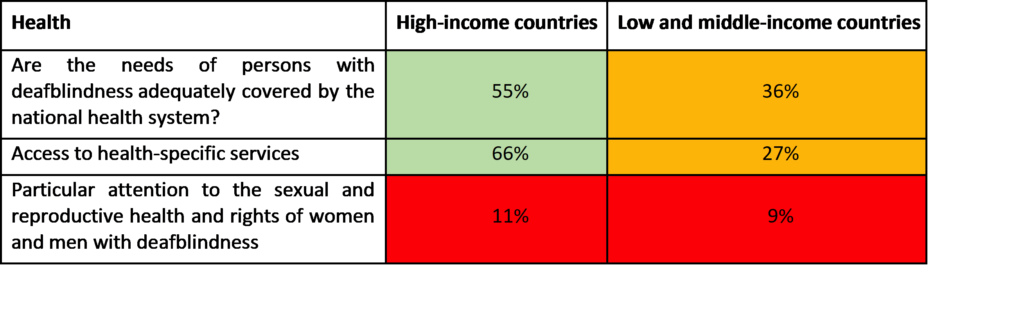

The survey indicates that health seems to be more accessible for persons with deafblindness than education, especially in high-income countries. Two-thirds of respondents from high-income countries reported having access to specific health services compared to only 27% in lower-income countries. However, both high and low-income countries are reported to be failing persons with deafblindness in terms of sexual and reproductive health services.

The consultation undertaken at the 2018 Helen Keller World Conference provided a more detailed picture of healthcare for persons with deafblindness, highlighting several key issues:

- Medical professionals lack knowledge about the causes and specificity of deafblindness, particularly in children, which leads to poor early identification and intervention.

- Healthcare staff also lack knowledge about the specific communication requirements of persons with deafblindness, which often leads to professionals talking to interpreter-guides or family members rather than the person themselves. This can have a serious impact, including misdiagnosis, as the person is unable to explain his or her symptoms. Furthermore, persons with deafblindness are unable to access information about proposed treatment, leading to a limited understanding of their own medical history.

- In emergency situations, health providers often have no idea how to communicate with a person with deafblindness. This means that the experience can be extremely frightening and/or violating for the person, who does not know what is happening.

- Health promotion and prevention campaigns, for example on immunisation, non-communicable diseases and HIV/Aids, are often inaccessible.

- The profound isolation and lack of socialisation experienced by persons with deafblindness can result in severe distress. A lack of adequate mental health support and services exacerbates this issue.

WFDB members shared good practice that tackle issues linked to access to health in different countries. Several interesting initiatives emerged, including:

- In Denmark, the Association for the Deafblind provides its members with personalised cards stipulating their communication requirements and needs. These can then be placed on a hospital bed in case of emergency, alerting providers to their needs. Information kits on deafblindness have also been distributed to health providers.

- In Sweden, the government has organised a deafblindness ‘team’ to provide support on health, rehabilitation and social inclusion, with a specific focus on mental health.

- Australia has a national booking service that enables persons with deafblindness to book interpreter-guides when using health facilities. Whilst effective, this system works better in private than public practice.

- In Mexico, a training course has been developed to support interactions between nurses and persons with deafblindness. A training workshop on basic communications systems has also been offered to student nurses at the university. Due to its success, the approach will be replicated in the future.

- In Tanzania, Romania, Kenya, Uganda, and India, Sense international has developed early detection and intervention programs (see page 33).

- In Malawi, VIHEMA Deafblind has led a pilot project on access to sexual and reproductive health (see below).

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Provide adequate training to healthcare staff both on the causes of deafblindness and the specific communication requirements of persons with deafblindness.

- Ensure access to adequate sexual and reproductive health services, with an emphasis on women and girls with deafblindness.

- Ensure the provision of adequate early detection and intervention services, in partnership with education providers.

- Ensure the adequate provision of interpreter-guides.