WHAT DOES THE DATA SAY?

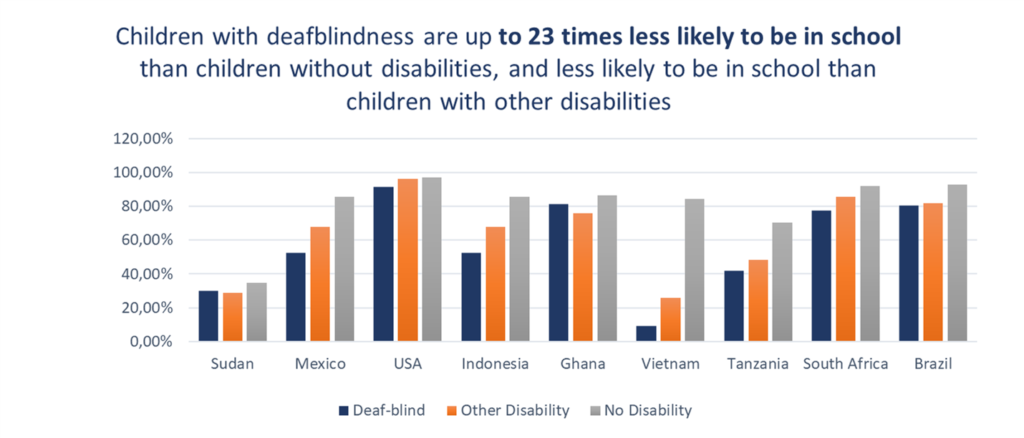

Excluding Uruguay and Ireland due to the small sample sizes, nine datasets provided evidence on school enrolment among children with deafblindness aged 5 to 17 years. Children with deafblindness were statistically less likely to be in school than children without disabilities across each of the datasets, with the biggest gaps in enrolment in Mexico (33% gap), Indonesia (62%) and Vietnam (75%).

In eight of the nine datasets considered (excluding Brazil), children with deafblindness were also statistically less likely to be in school than children with other disabilities. The gap in enrolment between children with deafblindness and children with other disabilities was largest in Mexico (15%), Indonesia (15%) and Vietnam (16%). There was no difference in the proportion of girls and boys with deafblindness attending school.

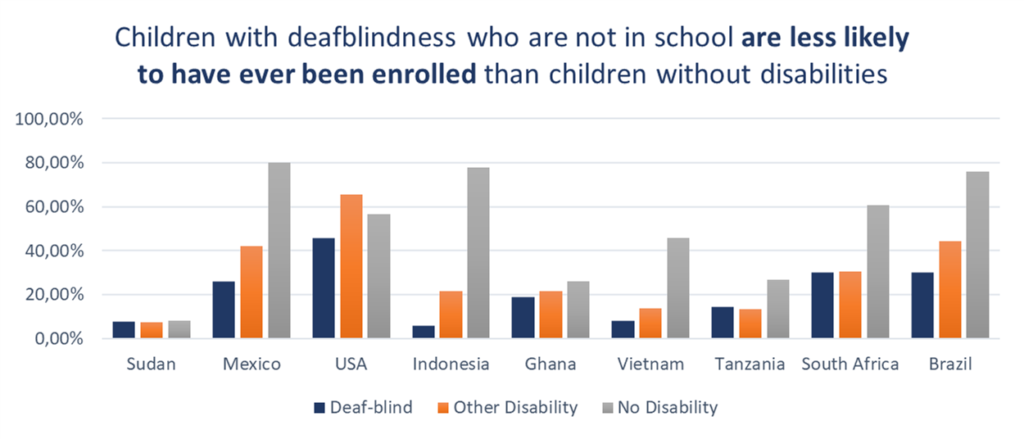

Of those children aged 5 to 17 who were not enrolled in school, children with deafblindness were less likely to have ever previously been enrolled than children without disabilities in seven of the nine datasets.

They were also less likely to have ever been enrolled in school than children with other disabilities in four of the datasets. However, due to the small sample size, some findings have wide confidence intervals and should be interpreted with caution.

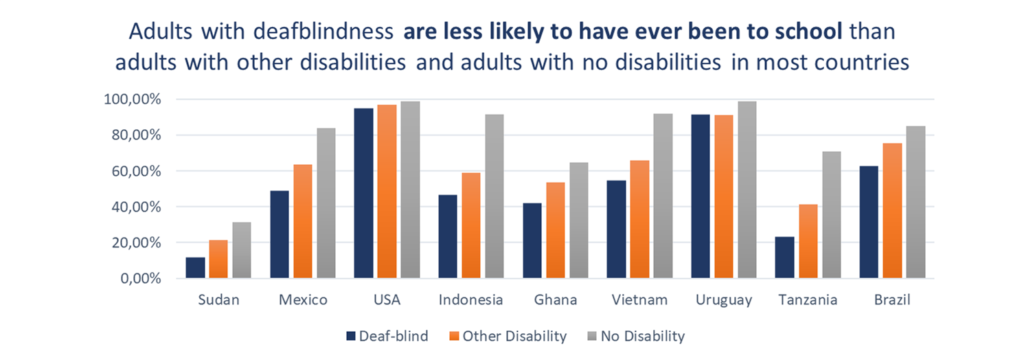

Adults with deafblindness were less likely to have attended school as children than adults with other disabilities and adults without disabilities in each dataset. After accounting for age and gender (given that adults with deafblindness are likely to be older than adults without disabilities), this finding was still statistically significant in all datasets, with the exception of Mexico and Uruguay, where there was no significant difference between adults with deafblindness and those with other disabilities. Considering that age of onset is likely to have been after the completion of education for many adults with deafblindness, this may be due to adults with lower socio-economic status being less likely to attend school or seek healthcare for functional limitations related to ageing.

It is important to note that evidence from the country analyses does not provide an indication of the quality of education children with deafblindness receive. Findings from the literature review, which primarily features studies from the United States, raises concerns regarding the quality of education for children with deafblindness. As deafblindness in children and young adults is rare, most educational professionals receive little, if any, training or support to work with students with deafblindness [22, 23]. Learners with deafblindness are also a very heterogeneous group, so teaching and learning strategies may vary greatly between individuals. For example, strategies can depend on whether deafblindness is pre-lingual or post-lingual, and the level of hearing and visual impairment [10]. Furthermore, many children and young adults with deafblindness have additional disabilities, which require extra learning support [24, 25]. Early identification and referral to programmes for infants and young children with deafblindness is essential for improving educational, as well as cognitive and social, outcomes [24, 26]. However, delays in accessing services are common. For example, across different states in the United States, only 0-26% of children with deafblindness were referred to appropriate services before the age of three [26]. These issues are likely to be even more pronounced in low and middle-income settings where there has been less investment in inclusive education.

OUR VOICE

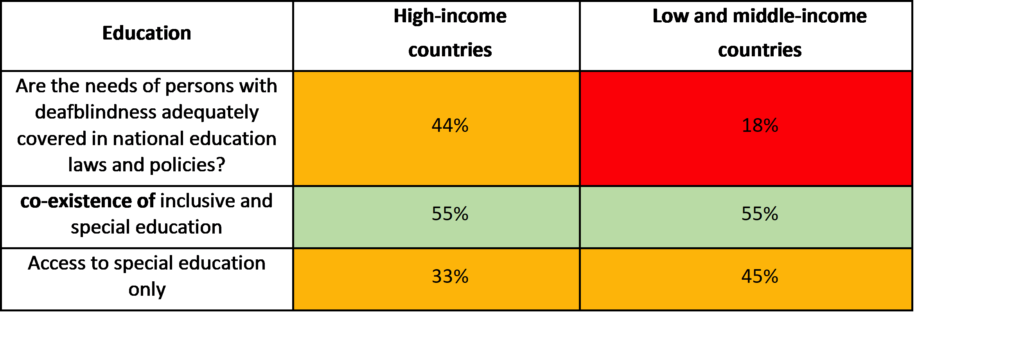

Education is a key issue for WFDB members. They identified strong links between employability, social participation and the educational opportunities accessible to children and young persons with deafblindness. Whilst the situation is more pronounced in low-income countries, less than half of the respondents from high-income countries consider education policies to adequately cover the needs of children with deafblindness. In more than half of the countries included within this study, governments provide a mix of special and inclusive education. A third of high-income countries, and nearly half of lower income countries, however, only provide special education.

Discussions that took place during the 2018 Helen Keller World Conference highlighted several issues:

- In many countries, a lack of awareness about deafblindness results in both families and institutions failing to recognise the right of children with deafblindness to go to school, and that education obligations apply to all children, regardless of disability.

- A lack of early identification and intervention programmes means that parents do not learn to communicate with their children. This makes it more difficult for parents to understand and accept their child’s disability, as well as to access support. This, in turn, impacts on a child’s development.

- In the majority of countries, there is limited data on the numbers of children with deafblindness in or out of school.

- In many countries, there are no specific educational support programmes for children and young people with deafblindness. Indeed, the majority of support initiatives are either only for deaf or blind children. Teachers are not adequately trained and there is no adaptation of curricula. Members referenced numerous education policies that did not consider children with deafblindness. Existing schools for blind or deaf children may or may not support children with deafblindness; however, there is no systematic approach.

- While specific support services might be available in some high-income countries, these opportunities are unlikely to be available in the majority of low and middle-income countries. There are also discrepancies within countries, with services predominantly concentrated in the capital or major cities, but not in rural areas or smaller towns.

- The importance of developing formal and non-formal education services for young people and adults with deafblindness who did not have access to educational opportunities as children.

Whilst the vast majority of WFDB members support and are in favour of inclusive education, many also call for the further development of resource centres for children with deafblindness, which provide communication, mobility and daily living skills, and prepare children for school. In some countries, resource centres collaborate with mainstream schools and support teachers who have pupils with deafblindness, training them in communication and pedagogy adaptation.

Community-based programmes also provide initial support to children in their homes to prepare them for school and to raise awareness and confidence amongst parents. WFDB members insisted on the importance of developing links between schools, families and communities to ensure the inclusion of children with deafblindness.

It was also suggested that, in some countries, it might be easier to obtain adequate support in private schools rather than public sector institutions, which increases the inequalities faced by poorer families.

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Ensure that the requirements of persons with deafblindness are taken into account in inclusive education laws, policies and programmes, and efforts are made to adapt curricula, train teachers and provide support to students.

- Ensure the availability of resource centres that support mainstream schools, children with deafblindness and their families.

- Ensure the adequate provision of interpreter-guides.