WHAT DOES THE DATA SAY?

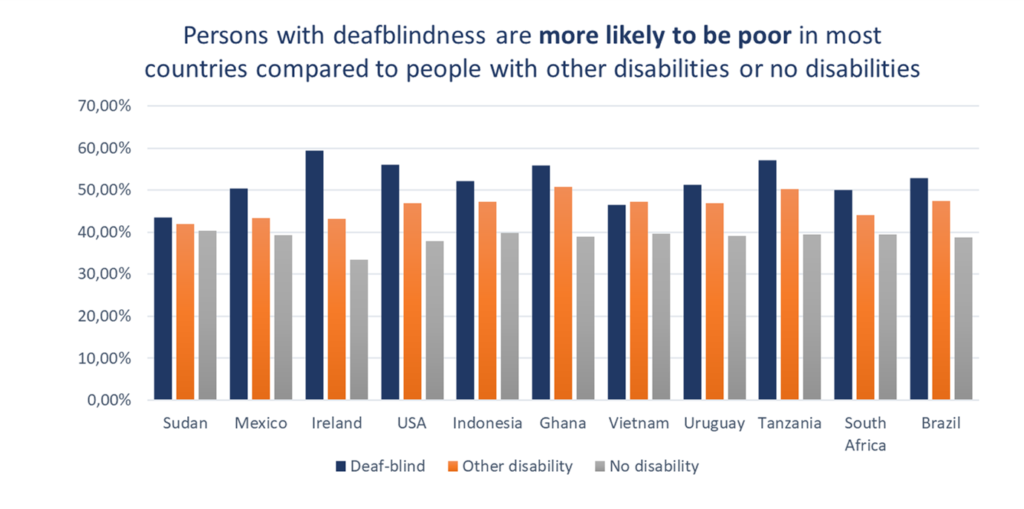

The majority of the studies included in the literature review did not provide evidence on the socio-economic status of people living with deafblindness. In all 11 countries covered by the data analysis, households that included persons with deafblindness were more likely to be in the bottom 40% in terms of socio-economic status compared to households with no members with disabilities[1] (Figure 6). The gap in poverty was most pronounced in Ireland (25.9%), the United States (18.9%), Ghana (16.9%) and Tanzania (17.6%). Differences were statistically significant after adjusting for household characteristics (e.g. size, age structure and location) in all countries, with the exception of Vietnam. Compared to people with other disabilities, persons with deafblindness were statistically more likely to be in the bottom 40% in all countries except Vietnam, Sudan and Tanzania. Households containing younger adults with deafblindness (aged 50 years and under) were more likely to be living in poverty in five countries (Brazil, South Africa, Vietnam, the United States and Indonesia).

This indicates that persons of working age with deafblindness may be more greatly affected by poverty. In Vietnam, households that included members with other disabilities were marginally more likely to be poor in comparison to households that included family members with deafblindness.

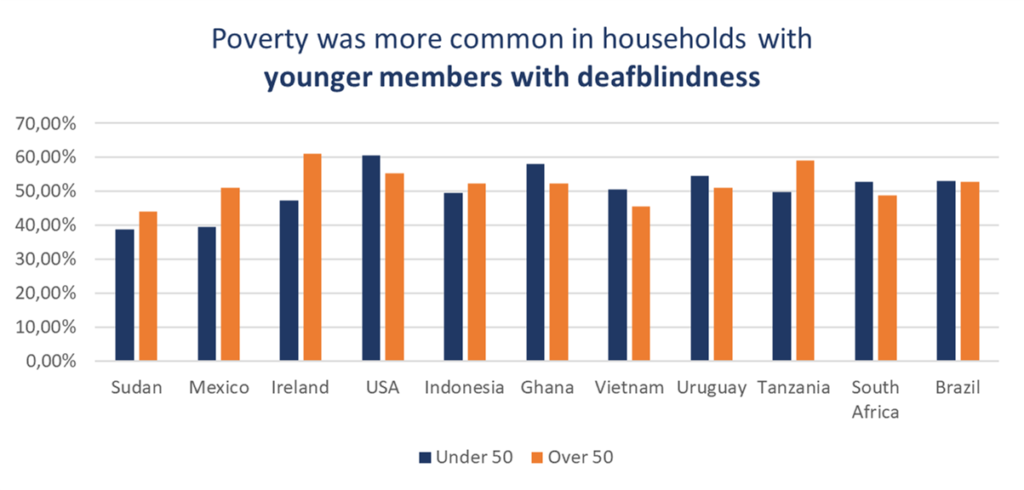

In disaggregating poverty by the age of the household member with deafblindness (<50 years or 50+ years), households including younger adults with deafblindness (under 50 years) were statistically more likely to be living in poverty in five countries (Brazil, South Africa, Vietnam, the United States and Indonesia) (Figure 7). This suggests that younger persons with deafblindness may have a greater impact on the situation of the household.

OUR VOICE

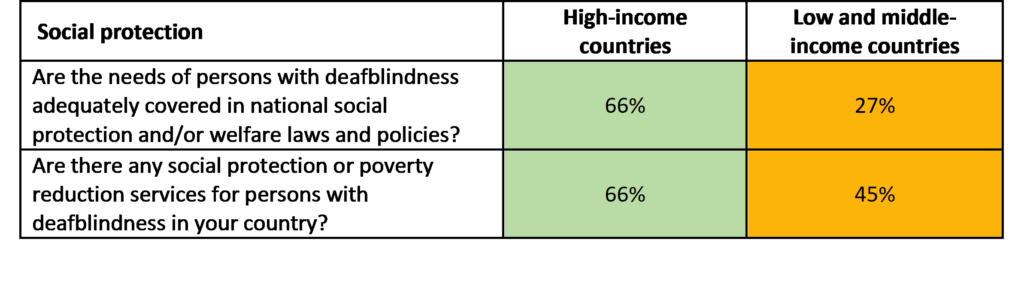

Unsurprisingly, the survey revealed that high-income countries offer better social protection support in comparison to low and middle-income nations. WFDB members reported that, when programmes are in place to support persons with disabilities, they benefit from them. Whilst issues exist with regards to disability assessment and determination processes, such as the need for two different certificates related to sight and hearing impairments, as outlined in section 1, this does not impede access to benefits.

In low and middle-income countries, as well as some high-income nations, social protection benefit schemes tend to focus on basic poverty-related issues and do not cover the extra costs related to interpretation or mobility challenges. As a result of limited service provision and low social benefits, persons with deafblindness cannot afford the support they need. One of the key issues is that policymakers do not view support services and assistive technology as a ‘fundamental need’, and consider them luxuries in comparison to shelter and food. However, these services are essential for daily living, especially for persons with deafblindness who have high support needs.

In addition, the majority of disability and/or welfare benefits are conditioned on the basis of either being labelled incapable to work or on an income threshold. As such, a person with deafblindness seeking to work would not receive support to pay for transport or the extra cost of accommodation, factors that are rarely, if ever, covered by employers.

Poverty Trap: The Impact of Disability-Related Costs on Persons with Deafblindness And Their Families

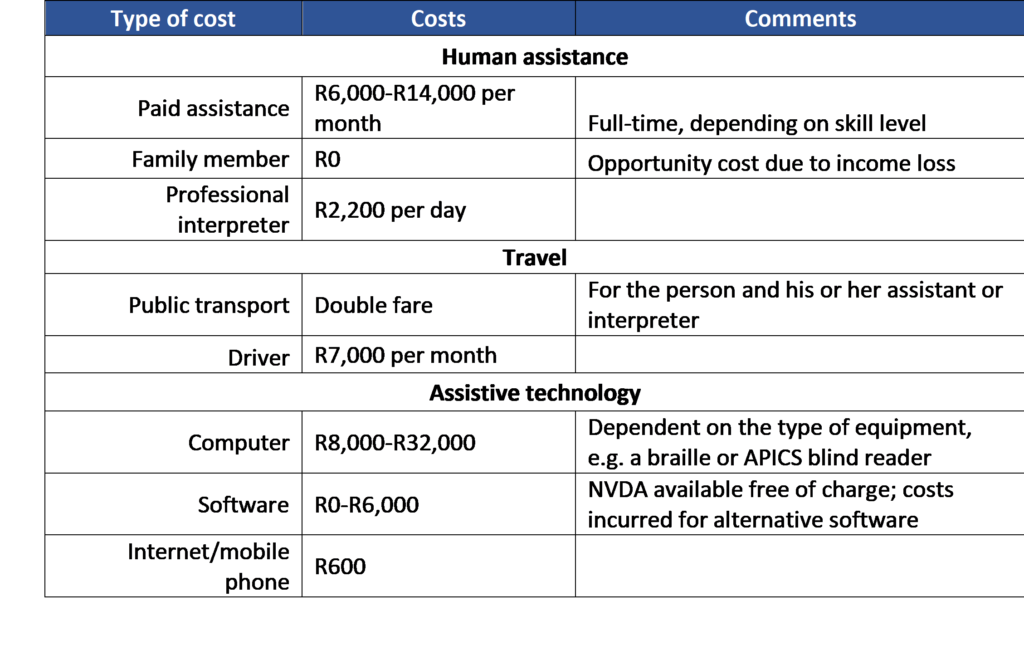

An innovative South African study on the extra costs of disability (DSD, 2014) illustrated the significant cost impact of disability for persons with deafblindness and their families. The cost of assistive devices to enable communication, for example, was highest for persons with deafblindness. Personal assistance costs were also among the highest.

Considering that, in 2014, the monthly disability grant was R1,340 per month, the majority of persons with deafblindness would not be able to afford such assistance. Consequently, a family member would have to stay at home to support the person, incurring an opportunity cost, which was amongst the highest for all groups of persons with disabilities. The table below outlines the range of costs identified by the study (this list is not exhaustive).

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Disability determination and eligibility processes should consider persons with deafblindness as a distinct disability group.

- Disability schemes should take into consideration the significant extra cost of deafblindness, including assistive technology, personal assistance and interpreter-guide services.